Which factors affect annual stool-based screening adherence and follow-up colonoscopy adherence among individuals who screen by stool testing?

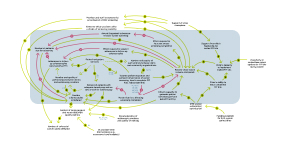

This CLD contains two important balancing loops related to screening/testing recommendations for individuals who complete stool testing. Specifically, for stool-based screening to be effective at detecting CRC, patients must 1) adhere to annual rescreening and 2) adhere to follow-up colonoscopies if their stool test is positive.

In the first balancing loop (B1), the more stool-based screens completed, the more effort is required to increase annual screening completion for each individual,290, 294 which decreases annual adherence to stool-based testing. Low annual adherence to stool-based testing increases the number of patients due for CRC screening, which should increase the number of routine stool-based screens completed.

In the second balancing loop (B2), the more stool-based screens completed, the more effort is required to increase adherence to follow-up colonoscopies,278, 290, 292 which decreases adherence to follow-up colonoscopies. Lower adherence to follow-up colonoscopies decreases the number of CRC cases detected.

The implementation of patient navigation (PN) services facilitates and strengthens partnerships between endoscopy providers and clinics, which increases follow-up colonoscopy adherence. PN also increases follow-up colonoscopy adherence directly88, 244 and increases patient education and outreach.41, 42, 99, 101 More patient education and outreach decrease patient barriers to screening completion, which increases the number of stool-based tests completed.38, 39, 87, 88, 136, 137, 163-165, 274, 427, 456 Tailored patient education and outreach also increases the number of stool-based tests completed directly.4, 6, 28, 274

Cited references for this diagram

For screening promotion, grantees reported navigators as having made reminder calls for colonoscopy appointments (83%) and assisted patients in accessing bowel preparation materials (83%). Only 56% of grantees reported that navigators made reminder calls to encourage patients to return FOBT or fecal immunochemical test (FIT) tests, although this may reflect fewer programs working with FOBT/FIT testing.

Escoffery C, Fernandez ME, Vernon SW, Liang S, Maxwell AE, Allen JD, Dwyer A, Hannon PA, Kohn M, DeGroff A. Patient Navigation in a Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015 Sep-Oct;21(5):433-40. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000132. PMID: 25140407; PMCID: PMC4618371.

Also, despite LFC staff providing education about the importance of screening, patients may have had significant competing priorities. Experiencing homelessness posed difficulties in maintaining contact for follow-up. Comorbidities, such as mental health and substance use issues frequently experienced with homelessness (Wadhera et al., 2019), may also be a barrier to completing CRC screening.

Hardin V, Tangka FKL, Wood T, Boisseau B, Hoover S, DeGroff A, Boehm J, Subramanian S. The Effectiveness and Cost to Improve Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Federally Qualified Homeless Clinic in Eastern Kentucky. Health Promot Pract. 2020 Nov;21(6):905-909. doi: 10.1177/1524839920954165. Epub 2020 Sep 29. PMID: 32990049; PMCID: PMC7894067.

According to representatives from LFC, there may be additional barriers facing LFC’s patient population related to transportation and lack of privacy for bowel prep prior to the colonoscopy.

Hardin V, Tangka FKL, Wood T, Boisseau B, Hoover S, DeGroff A, Boehm J, Subramanian S. The Effectiveness and Cost to Improve Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Federally Qualified Homeless Clinic in Eastern Kentucky. Health Promot Pract. 2020 Nov;21(6):905-909. doi: 10.1177/1524839920954165. Epub 2020 Sep 29. PMID: 32990049; PMCID: PMC7894067.

In this study, based on retrospective self-reports, patients spent, on average, 23.7 h preparing for, traveling for and having a colonoscopy, and an additional 5.1 h, on average, recovering from the colonoscopy. This translated into a total cost of $335.95 for the patient in lost time and $79.03 for the caregiver. In addition, an estimated $17.46 was incurred in travel and other costs. Even when colonoscopy is provided free of charge to the patient, additional costs may be incurred which could be a significant barrier for low income individuals to receive CRC screening.

Hoover S, Subramanian S, Tangka FKL, Cole-Beebe M, Sun A, Kramer CL, Pacillio G. Patients and caregivers costs for colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening: Experience of low-income individuals undergoing free colonoscopies. Eval Program Plann. 2017 Jun;62:81-86. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.01.002. Epub 2017 Jan 7. PMID: 28153341; PMCID: PMC5847315.

Overall, the total cost of undergoing a “free” colonoscopy screening is substantial for a low-income patient, especially when the average hourly wage estimate used in this analysis for the patient was $11.68. This relatively high cost could explain the reason for the lower levels of compliance with screening recommendations among people with low education and generally low socioeconomic status (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013).

Hoover S, Subramanian S, Tangka FKL, Cole-Beebe M, Sun A, Kramer CL, Pacillio G. Patients and caregivers costs for colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening: Experience of low-income individuals undergoing free colonoscopies. Eval Program Plann. 2017 Jun;62:81-86. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.01.002. Epub 2017 Jan 7. PMID: 28153341; PMCID: PMC5847315.

Financial incentives should be included in future assessments of health promotion interventions, as colonoscopy screening requires a substantial time commitment and the cost of lost time is significant, especially for the low-income population.

Hoover S, Subramanian S, Tangka FKL, Cole-Beebe M, Sun A, Kramer CL, Pacillio G. Patients and caregivers costs for colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening: Experience of low-income individuals undergoing free colonoscopies. Eval Program Plann. 2017 Jun;62:81-86. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.01.002. Epub 2017 Jan 7. PMID: 28153341; PMCID: PMC5847315.

Follow-up of positive stool tests with colonoscopy is known to be challenging. A recent systematic review of interventions to improve follow-up found that patient navigators and provider reminders or performance data may help improve follow-up rates.

Nadel MR, Royalty J, Joseph D, Rockwell T, Helsel W, Kammerer W, Gray SC, Shapiro JA. Variations in Screening Quality in a Federal Colorectal Cancer Screening Program for the Uninsured. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019 May 30;16:E67. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180452. PMID: 31146803; PMCID: PMC6549419.

Sites responded to slow early recruitment by developing more tailored outreach and education, some specifically geared toward men, partnering with existing referral services, expanding partnerships with primary care networks, improving and systematizing the patient enrollment process, and broadening and/or changing the screening test options.[[2,9,11,12]]

Seeff LC, DeGroff A, Joseph DA, Royalty J, Tangka FK, Nadel MR, Plescia M. Moving forward: using the experience of the CDCs' Colorectal Cancer Screening Demonstration Program to guide future colorectal cancer programming efforts. Cancer. 2013 Aug 1;119 Suppl 15:2940-6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28155. PMID: 23868488.

The well-defined patient pathways, clinical protocols, quality assurance, and tracking systems to guide referral through diagnostic follow-up were critical facilitators in mid- and late implementation.[[13]]

Seeff LC, DeGroff A, Joseph DA, Royalty J, Tangka FK, Nadel MR, Plescia M. Moving forward: using the experience of the CDCs' Colorectal Cancer Screening Demonstration Program to guide future colorectal cancer programming efforts. Cancer. 2013 Aug 1;119 Suppl 15:2940-6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28155. PMID: 23868488.

Respondents also described the challenge of receiving incomplete or incorrectly completed FIT tests due to patient misunderstanding around instructions to complete FIT testing which could have occurred because of cultural/linguistic barriers or a breakdown in communication when patients do not receive instructions in person.

Arena L, Soloe C, Schlueter D, Ferriola-Bruckenstein K, DeGroff A, Tangka F, Hoover S, Melillo S, Subramanian S. Modifications in Primary Care Clinics to Continue Colorectal Cancer Screening Promotion During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Community Health. 2023 Feb;48(1):113-126. doi: 10.1007/s10900-022-01154-9. Epub 2022 Oct 29. PMID: 36308666; PMCID: PMC9617236.

The CRCSDP programs that screened with FOBT faced challenges in all these areas, with low card return rates (53%), lower-than-desired rates of follow-up testing for positive FOBT tests (84%), and low rates of rescreening (13%-16%).[[2,3]]

Seeff LC, DeGroff A, Joseph DA, Royalty J, Tangka FK, Nadel MR, Plescia M. Moving forward: using the experience of the CDCs' Colorectal Cancer Screening Demonstration Program to guide future colorectal cancer programming efforts. Cancer. 2013 Aug 1;119 Suppl 15:2940-6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28155. PMID: 23868488.

Based on the evaluation of this program, we observed challenges associated with both FOBT (substantial loss to follow-up) and colonoscopy (higher program costs translating into fewer people screened).

Seeff LC, DeGroff A, Joseph DA, Royalty J, Tangka FK, Nadel MR, Plescia M. Moving forward: using the experience of the CDCs' Colorectal Cancer Screening Demonstration Program to guide future colorectal cancer programming efforts. Cancer. 2013 Aug 1;119 Suppl 15:2940-6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28155. PMID: 23868488.

Our finding that clinics primarily using FIT tests or providing free fecal kits were associated with lower screening rates might represent a relationship between clinics preferring FIT tests and clinics with lower screening rates (such as FQHCs). Additionally, assuring annual FIT testing may be more difficult in contrast to colonoscopy which is required only once each 10 years.

Sharma KP, DeGroff A, Scott L, Shrestha S, Melillo S, Sabatino SA. Correlates of colorectal cancer screening rates in primary care clinics serving low income, medically underserved populations. Prev Med. 2019 Sep;126:105774. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105774. Epub 2019 Jul 15. PMID: 31319118; PMCID: PMC6904949.

Overall, the majority of patient barriers and navigation activities delivered by BCC and CRC PNs were related to personal and cultural factors. Clearly, lack of awareness and education about cancer screening continue to be significant barriers among populations served by NBCCEDP and CRCCP.

Barrington WE, DeGroff A, Melillo S, Vu T, Cole A, Escoffery C, Askelson N, Seegmiller L, Gonzalez SK, Hannon P. Patient navigator reported patient barriers and delivered activities in two large federally-funded cancer screening programs. Prev Med. 2019 Dec;129S:105858. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105858. Epub 2019 Oct 22. PMID: 31647956; PMCID: PMC7055651.

Specifically, highly reported patient barriers among BCC and CRC PNs included lack of: knowledge about cancer; knowledge about cancer screening procedures; knowledge about the benefit of screening; motivation to get screened; transportation; and health insurance.

Barrington WE, DeGroff A, Melillo S, Vu T, Cole A, Escoffery C, Askelson N, Seegmiller L, Gonzalez SK, Hannon P. Patient navigator reported patient barriers and delivered activities in two large federally-funded cancer screening programs. Prev Med. 2019 Dec;129S:105858. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105858. Epub 2019 Oct 22. PMID: 31647956; PMCID: PMC7055651.

With improved tracking and automated reminder systems, mailed FIT kits paired with tailored patient education and clear instructions for completing the test may help primary care clinics catch up on the backlog of missed screenings during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Arena L, Soloe C, Schlueter D, Ferriola-Bruckenstein K, DeGroff A, Tangka F, Hoover S, Melillo S, Subramanian S. Modifications in Primary Care Clinics to Continue Colorectal Cancer Screening Promotion During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Community Health. 2023 Feb;48(1):113-126. doi: 10.1007/s10900-022-01154-9. Epub 2022 Oct 29. PMID: 36308666; PMCID: PMC9617236.

Currently, CDC's patient navigation policy requires that PNs deliver the following six activities: 1) assessment of patient's barriers to cancer screening, diagnostic services, or initiation of cancer treatment; 2) patient education and support; 3) resolution of patient barriers; 4) patient tracking and follow-up over at least two patient contacts to monitor completion of screening and diagnostic testing and treatment initiation; 5) collection of outcomes related to patient navigation (e.g., adherence to screening, diagnostic testing, and treatment); and 6) collection of patient-reported outcomes related to cancer screening, diagnosis, or treatment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, 2019)

Barrington WE, DeGroff A, Melillo S, Vu T, Cole A, Escoffery C, Askelson N, Seegmiller L, Gonzalez SK, Hannon P. Patient navigator reported patient barriers and delivered activities in two large federally-funded cancer screening programs. Prev Med. 2019 Dec;129S:105858. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105858. Epub 2019 Oct 22. PMID: 31647956; PMCID: PMC7055651.

Specifically, highly reported navigation activities among BCC and CRC PNs included: talking to patients in clinics about screening; providing one-on-one education; and assessing patient barriers to screening.

Barrington WE, DeGroff A, Melillo S, Vu T, Cole A, Escoffery C, Askelson N, Seegmiller L, Gonzalez SK, Hannon P. Patient navigator reported patient barriers and delivered activities in two large federally-funded cancer screening programs. Prev Med. 2019 Dec;129S:105858. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105858. Epub 2019 Oct 22. PMID: 31647956; PMCID: PMC7055651.

Systematic reviews have identified barriers to CRC screening including low levels of education, language or communication issues, low socioeconomic status, lack of insurance coverage, and general attitudes towards prevention (for example, smokers are less likely to seek screening) (Gimeno Garcia, 2012; Subramanian et al., 2004).

Tangka FKL, Subramanian S, Hoover S, Royalty J, Joseph K, DeGroff A, Joseph D, Chattopadhyay S. Costs of promoting cancer screening: Evidence from CDC's Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP). Eval Program Plann. 2017 Jun;62:67-72. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.12.008. Epub 2016 Dec 12. PMID: 27989647; PMCID: PMC5840873.

The patient navigator identified barriers (N=148) to patients being screened for colorectal cancer or other cancers. The largest categories of barriers identified included financial or insurance issues (30.4%, 45/148); psychosocial issues, such as fear of the test and fear of test outcome (23.6%; 35/148); and transportation (23.6%; 35/148).

Tangka FKL, Subramanian S, Hoover S, Cariou C, Creighton B, Hobbs L, Marzano A, Marcotte A, Norton DD, Kelly-Flis P, Leypoldt M, Larkins T, Poole M, Boehm J. Improving the efficiency of integrated cancer screening delivery across multiple cancers: case studies from Idaho, Rhode Island, and Nebraska. Implement Sci Commun. 2022 Dec 16;3(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00381-4. PMID: 36527147; PMCID: PMC9756516.

Increased patient education and engagement emerged as a modification to address challenges around receipt of completed FIT kits that did not adhere to requirements and were, therefore, unusable because they were missing the collection date or received more than 14 days after the sample was collected.

Arena L, Soloe C, Schlueter D, Ferriola-Bruckenstein K, DeGroff A, Tangka F, Hoover S, Melillo S, Subramanian S. Modifications in Primary Care Clinics to Continue Colorectal Cancer Screening Promotion During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Community Health. 2023 Feb;48(1):113-126. doi: 10.1007/s10900-022-01154-9. Epub 2022 Oct 29. PMID: 36308666; PMCID: PMC9617236.

Patient navigation (PN) has emerged as an important approach to reduce cancer disparities by addressing barriers to cancer care.

Escoffery C, Fernandez ME, Vernon SW, Liang S, Maxwell AE, Allen JD, Dwyer A, Hannon PA, Kohn M, DeGroff A. Patient Navigation in a Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015 Sep-Oct;21(5):433-40. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000132. PMID: 25140407; PMCID: PMC4618371.

However, some recent studies with more rigorous study designs have evaluated the effectiveness of PN in increasing CRC screening and found PN effective in addressing individual and system barriers to CRC screening faced by low-income, underserved populations,[[14–16]] improving screening quality, as well as follow-up and diagnostic care, for patients with abnormalities.[[17,18]]

Escoffery C, Fernandez ME, Vernon SW, Liang S, Maxwell AE, Allen JD, Dwyer A, Hannon PA, Kohn M, DeGroff A. Patient Navigation in a Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015 Sep-Oct;21(5):433-40. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000132. PMID: 25140407; PMCID: PMC4618371.

Specific to screening provision, grantees using colonoscopy as the primary test (n = 12) reported that their navigators made reminder calls for colonoscopy appointments and for bowel preparation (both 92%), assisted patients in accessing bowel preparation materials (83%), tracked patients to ensure the procedure was performed (92%), and made follow-up calls after the colonoscopy to check on patients (83%).

Escoffery C, Fernandez ME, Vernon SW, Liang S, Maxwell AE, Allen JD, Dwyer A, Hannon PA, Kohn M, DeGroff A. Patient Navigation in a Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015 Sep-Oct;21(5):433-40. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000132. PMID: 25140407; PMCID: PMC4618371.